I visited Bahrain for the first time in too many years this summer. On one day, we did a tour of historic mosques in the islands, visiting the resting places of Sheikh Maytham Al-Bahrani (Mahooz), Emir Zaid bin Sohan (Malchiyya), Sheikh Ahmed bin Sa’ada Al-Sitri Al-Bahrani (Sitra) and of course the Nabih Saleh. Each of those places and persons deserve their own story.

At Nabih Saleh, which is located on the island by the same name, we were lucky to meet the caretaker of the mosque. He gave us a tour of the place, its historic graves and the rock they were carved into and, most preciously, this little booklet: The Story of Nabih Saleh.

The booklet is intended as something of a visitor’s guide for the mosque and the shrine of Nabih Saleh. It was written in 1987 by Muhammad Ali Al-Nasiri (1919-1999). If you follow me on Instagram, you might know that I talk a lot about Al-Nasiri, who I consider to be one of the most important literary figures of 20th century Bahrain. Muhammad Ali Al-Nasiri was a Mullah (in Bahraini context a preacher, particularly around the stories of Ahlulbayt) and a poet. He was a student of Mullah Atiyya bin Ali Al-Jamri, my great-great-grandfather and one of the great religious poets of the Baharna, who popularised a form of dialect poetry that is still popularly recited today during religious events, particularly during Muharram and the ten days of mourning around Ashura.

It is for his work documenting culture that Al-Nasiri remains an essential literary figure. Last year’s issue of ArabLit Quarterly: FOLK featured his work, as both myself (“Waddle Like a Duck”) and Rawan Maki (“Wat Rainbow”) depended on his books collecting Bahrani folk poetry for our translations and articles. Al-Nasiri has books documenting Bahrain’s culture, folk poetry, jokes, colloquial sayings and more. And as a religious poet, we see him in many places. On the day of our tour, we first encountered a poem of Al-Nasiri that hangs above the shrine of Sheikh Maytham Al-Bahrani, and then bumped into him again in the shrine of Nabih Saleh. It is his great love and celebration of Bahraini and Bahrani culture that makes him so important twenty years on.

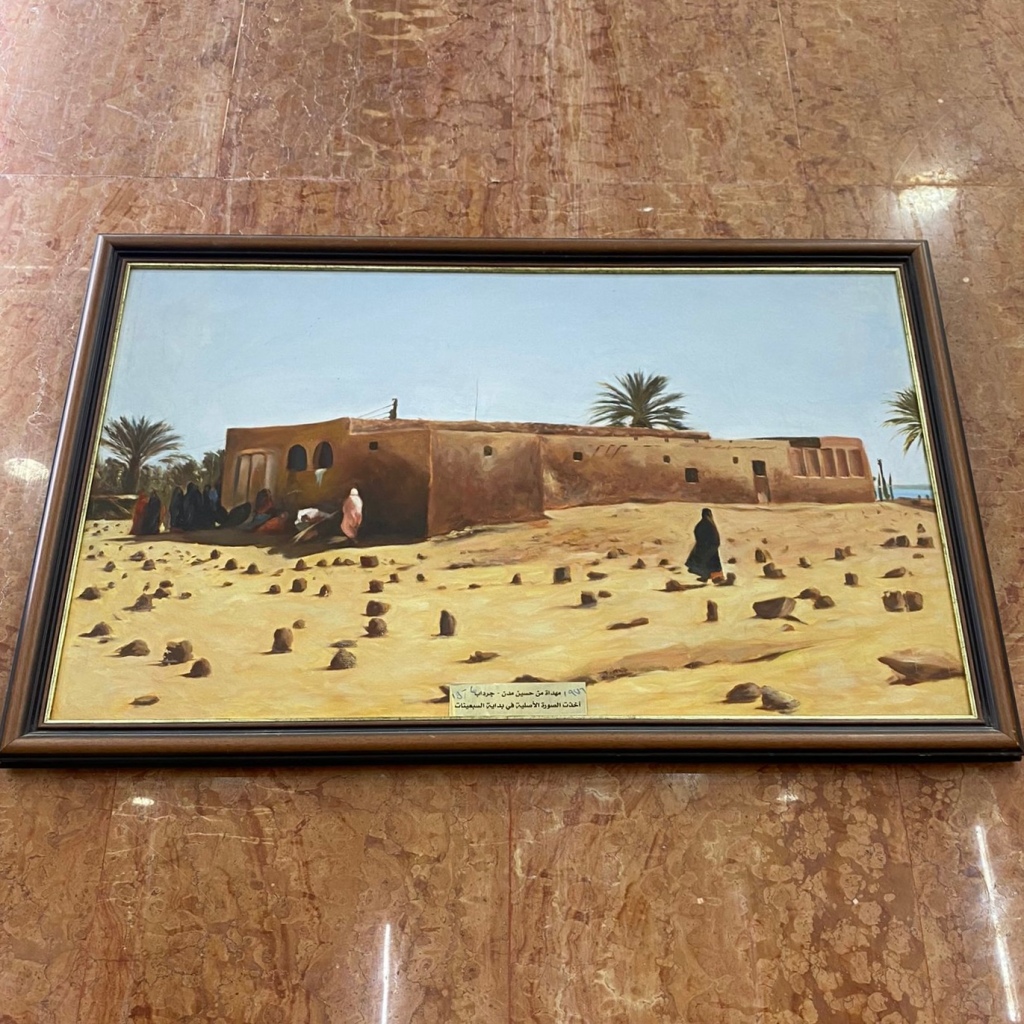

Nabih Saleh is a significant religious site for Bahrain. It was once on a secluded island just north of Sitra island and east of the main Bahrain island (Awal), though land reclamation has made it all one contiguous area. Until about 50 years ago, you could only reach Nabih Saleh by boat. There is little here except for the shrine. Back in the day, there was also a date grove and sales of its produce was used to maintain the ship that took pilgrims across. It was particularly an important site for female pilgrims as well. People would travel from far to have their prayers enhanced and fulfilled in this shrine. Tragedy has struck Nabih Saleh: in the 1940s, an overcrowded boat full of women and children capsized in the short journey to the island, with virtually no survivors. That event is recorded in a mournful poem by Mulla Atiyya, in which the poet demands answers from the sea, the wind and the ship captain for the avoidable tragedy – one which I hope to translate one day.

Pilgrims still attend to this day, and what is striking is how many of them are also non-Muslims – when we visited, there were two Hindu men respectfully attending the shrine, and people of all faiths frequently journey to pay respects to Nabih Saleh.

On the request of the shrine’s caretaker, Husain Al-Basri, I have translated the first two sections of Al-Nasiri’s booklet. The original text is longer than mine, as it includes two poems, some descriptions of other notable graves, and details on the shrine’s construction. But this is the juicy part.

Read on to discover the story of Nabih Saleh and the man it was named after.

Part 1: The Island of Nabih Saleh

Previously known as Ukul island, and as Nabih Saleh presently, this island is the hopeful stopping place for many people, among them the rulers and ulama (scholars) of past times. For the rulers, they saw this land’s fertile earth and bountiful springs, its plentiful date palms and fruitful trees. For the ulama, they were drawn to its isolation from the noisy clamour of people, for the pursuit of knowledge requires quiet.

In its past, Nabih Saleh was a popular intellectual market, both for the thinkers in it and beyond, from the surrounding villages, including Mahooz, Tubli, Sitra island and beyond, such that many great scholars emerged from it. Among them are Sheikh Ahmed Al-Mutawwaj (died 9th century AH, 15th century AD) who wrote many good works; Sheikh Dawood bin Hassan Al-Jaziri Al-Bahrani, whose school and resting place is close by the Nabih Saleh mosque and who is remembered in the book Anwar al-Badrayn: “He wrote many books with his blessed hand and held a library of some four hundred texts in the madrasa he ran from his home on the island.” One of Sheikh Dawood’s books, Tarteeb Al-Ma’ani, written in the 10th century AH (16th century AD), was found as far away as in Surat in India.

The number of graves for ulama in this little island is very large. There are, for example, the graves of Sheikh Abdullah Al-Mutawwaj, his son Sheikh Ahmed, his son Sheikh Naser Al-Mutawwaj, Sheikh Dawood and his son, Sheikh Ali. They are buried in the room adjacent to Nabih Saleh’s grave, which is the crown of these graves, renowned and celebrated. It stands like a tower on this island named after God’s good servant, Nabih Saleh, whose reputation spread east and west, and has become a shrine visited by people near and far across the Gulf.

Part 2: The Story of Nabih Saleh

The story passed down is this: The Nabih Sheikh Saleh, who is buried on Ukul island, would attend Friday prayer behind one of the learned men of this island. At this mosque, he would usually only attend the sunset, evening, and morning prayers. He would not attend the noon and afternoon prayer.

There came a day when his wife complained to the local Alim (a religious scholar who leads prayers and resolves disputes in accordance with Islamic law) about her husband. Nabih Saleh’s wife said: “Three nights a week, my husband leaves our home after dark and does not return until after the morning prayer. I don’t know where he goes. When I ask him, he refuses to speak and does not answer my questions.” The Alim promised to investigate the matter.

That evening, after prayers, the Alim called Nabih Saleh and informed him of his wife’s complaint. The Alim said: “You know she has rights to know about your activities, unless it was that you were to have a second wife.” Nabih Saleh did not reply.

When Nabih Saleh tried to leave home that night, his wife blocked his way. She said, “Will you not follow the Alim’s word and stop this? Or else, will you tell me the reason for your absence?” He said nothing and left.

The next day, she returned to the Alim and told him what happened. After the evening prayer, the Alim called Nabih Saleh again. He questioned him again and this time sternly added, “You are not ignorant to the consequences of your actions under Islamic law.” Sheikh Saleh bowed his head silently.

On the third occasion that this happened, the Alim threatened him openly for his actions and criticised his silence and refusal to answer. But when the Alim returned to his own home, he paused and thought about the reasons for Nabih Saleh’s insistence on his actions and refusal to speak. Perhaps, he thought, he is doing something he does not want his wife to know about.

The next morning, the Alim asked Nabih Saleh’s wife, “Which days of the week does he leave for his night-time activities?” She told him. On the next such night, he hid near Nabih Saleh’s home and followed him. Nabih Saleh took his normal path none the wiser of this pursuit. He entered the Ghuba mosque, on the island’s western seafront, and prayed two rak’as. Then he laid out his loincloth over the sea and swam across it. The Alim copied him and followed him across the sea, without Nabih Saleh’s knowing, until they reached the eastern shore of Tubli and the village of Jidd Ali.

Once on dry land, Nabih Saleh took his loincloth, cleaned it and carried it on his shoulder. The scholar copied him and followed him until they arrived on the western end of the village at the Haram Mosque, which was one of the seven mosques built with the guidance of Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib (AS) during his caliphate. There, a ring of learned men were sat waiting for him.

When they saw him, they called out, “The Sheikh has come, the Sheikh has come!” Then they said: “Sheikh of ours, you’ve come to us delayed tonight, have you not?”

He replied, “I was occupied, for this world hears and sees all things which people do not see.” Then Nabih Saleh gave a lecture on Islamic theology which was above the education of the Alim. His pursuer stayed and listened in rapt attention until the time came for the Night Prayer (Salat al-Layl). Nabih Saleh and his followers prepared for prayer, and the scholar took his chance to leave and return to Ukul the way he’d come. A huge respect and admiration for Nabih Saleh grew in him, and he felt deep shame for the way he had reprimanded him before.

When the time came for the morning prayer, the Alim attended his mosque, sat, and waited. The muezzin called for prayer, then told the Alim that the congregation was present for prayer. The Alim asked for Nabih Saleh, but the congregation said he was yet to arrive.

“We will wait for him,” said the Alim.

When Nabih Saleh came, the Alim asked him to come forward. “Come and lead the prayer,” he said.

But Nabih Saleh, showing great humility, replied, “No, I cannot pray in front of our sheikh.”

The Alim replied, “Yes you can. I was with you last night from beginning to end.”

When he heard this, Nabih Saleh opened his eyes, dazzled. He said: “You discovered what I was doing?”

The Alim said, “Yes.”

He replied, “You know that prayer is an obligation you must do at its proper hour.”

But the Alim insisted on his request. Nabih Saleh said: “If that is all you request, then I shall lead the prayer,” then he added in the Alim’s ear, “But if I should leave during the prayer, do not yourself leave until you and your followers prepare me.” The Alim was confounded by these words, but Nabih Saleh told him not to worry, then advised him with what he wanted.

Nabih Saleh led the prayer and finished it by prostrating and giving his gratitude to God that He may take his soul. As his prostration lasted so long, the congregation came and shook him, only to find him dead.

They washed his body and the Alim lead the funeral rites reverently. Sorrow and mourning spread and they buried him in the spot where his grave is to this day located. The Alim let the great loss of Nabih Saleh be known and spread the word about him, such that he came to be known by this nickname. Women prayed on Nabih Saleh’s behalf and God, listening, granted their prayers in honour of him. Knowledge of Nabih Saleh spread across the villages and towns of Bahrain and visitors seeking blessing came to visit his dignified resting place. This was roughly in the year 1191 AH (1777/1778 AD).

Translator’s Note

The island shrine and the person it was named after has two historic names. The first is Nabi Saleh, meaning Prophet Saleh. The nickname was given because of his great stature as a religious scholar but he was never believed to be an actual prophet by his followers, as all Muslims agree that the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) is the seal of prophets. In the 20th century, the name was adjusted to Nabih Saleh, meaning ‘Clever Saleh’ or ‘Insightful Saleh’, and we have used this name throughout.

One aspect not highlighted in Al-Nasiri’s telling is that in Islamic belief, humility, particularly with regards to charitable and good deeds, is held in extremely high regard. Part of Nabih Saleh’s greatness comes from his excessive humility, and his inability or refusal to show off, in any way, even to his wife, of the good deed he was doing. Hence, perhaps, that the Alim takes it upon himself to spread the word following his passing.

By Muhammad Ali Al-Nasiri, 1987

Translated by Ali Mansoor Al-Jamri, 2022